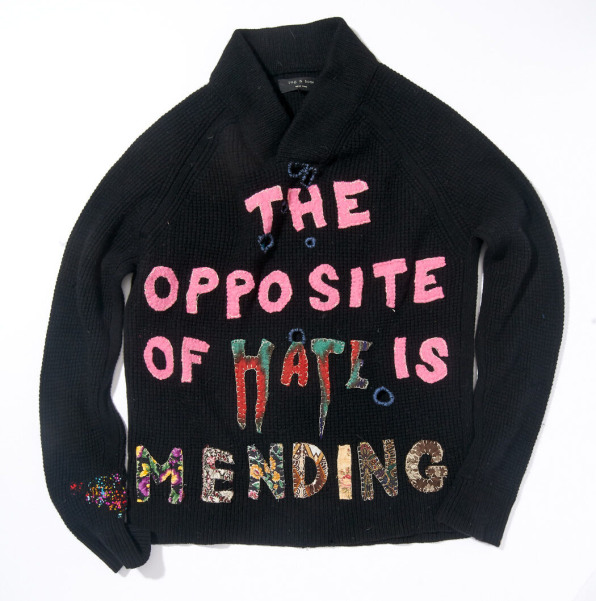

Changing the way we think about clothes is a revolutionary act.

Mending has baggage. Patched clothing speaks of shame and poverty and drudgery, even of slavery. But mending is a big word. It’s about repairing more than clothes. History, for example, which must be unpicked and remade, healing systemic injustice, making reparations, exposing scars. Clothes historians do this via what we wear, which turns out to be more important than we realized. Visible menders do it literally, by stitching new stories onto the worn fabric of our lives. They’re just clothes, but if enough people adopted more creative ways of sourcing, tending, and mending them, we’d fix much that’s wrong with the world.

Those who practice visible mending tend to be evangelists for a world outside the fashion-industrial complex, advocates of civil disobedience, feminists, antiracists—in short, humanists. If you lavish time and attention on nonessential embellishment, adding extra layers to a task that wouldn’t occur to most people, you are not doing it just for eco-warrior cred but as an opportunity. We personalize, extend the story, flag the beloved oldness, and render the item priceless.

You love clothes, but do you know where yours came from? I don’t mean Uniqlo or “stolen from my sister,” but their fundamental origins and what it all means. Clothes can be complicated creatures. They are not inert, but become unique with wear, even from the first time we take them for a ride, and then they gain in individuality with each outing. Our collections become extensions of us (“That dress is so you!”), combining in their own special, comforting ways and routinely performing magic tricks. Many of us own a results dress or lucky socks for sports, or a coat that’s gorgeous on the hanger but ghastly when worn. Clothes “change our view of the world and the world’s view of us,” wrote Virginia Woolf. The “why” of visible mending is all about that personal nature of clothes. And, while extending their lives, it also acknowledges their origins.

Getting dressed is a thing every person on the planet does—and we aren’t only doing it on the planet, we’re doing it to the planet. It’s not so much the megillions of clothes that already exist; the problem is the roughly 50 billion new garments made and sold each year. We don’t need them. Well, we do. We need fashion. Kind of.

To examine our need for this sort of über-clothing, let’s utilize that famous chart of human motivation, Abraham Maslow’s 1943 Hierarchy of Needs, a classification system expressed as a pyramid with society’s most universal primary requirements at the base, and self-actualization at the top: the pinnacle of fulfillment we can only pursue once we’ve taken care of all other necessities. Where does fashion, traditionally deemed unnecessary, really belong on the pyramid? At the base? Clearly, garments belong here to keep us warm and not arrested, but if we define fashion as clothing acquired for reasons other than protection, then that is not a fundamental need. Second tier? Wearing clothes that are apt for our circumstances can indeed be an aspect of personal safety, but it’s hard to argue that anyone is put in peril by dressing ugly or unhip.

Apparel is among the most polluting and exploitative of all industries. It creates 93.7 million pounds of waste each year and relies on the sweatshop labor of millions of people around the world, while Big Fashion tycoons rake in billions.

These gargantuan issues are insoluble by the likes of you and me. I’m just tired of fueling them, so I make tiny votes with my wallet. I haven’t bought a new garment (aside from underwear) in well over 10 years. Okay, I’m peculiarly in love with old clothes (did you notice?), but every time we resist auto-buying the temptingly cheap trend popping up on our feed, we are being a minor, but important, activist.

How we tend our textiles is as intimate and important as what we feed ourselves, and the industry that produces them—including all its tentacles (shipping, buildings, packaging, washing, etc.)—is even more damaging than food production, and may even prove to have as much planetary impact as fossil fuel. Renovating the way we dress is easier and cheaper than adopting an artisanal diet: Buying less and better, vintage curation, and the practices of community wardrobe are within everyone’s reach, not just elitist city dwellers.

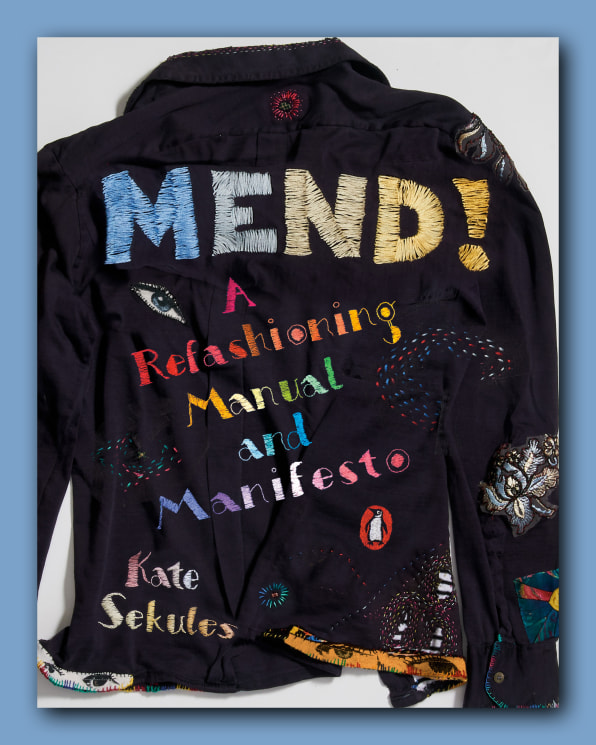

From MEND!: A Refashioning Manual and Manifesto by Kate Sekules, published by Penguin, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) 2020 by Kate Sekules.

"again" - Google News

September 14, 2020 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/3hu65Ay

The case for never buying new clothes again - Fast Company

"again" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YsuQr6

https://ift.tt/2KUD1V2

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The case for never buying new clothes again - Fast Company"

Post a Comment